I work in Residence Life. This means that there are several times of year when I spend more time on campus getting ready for students to arrive than I do with my family. Right now, for example, it’s almost 1 a.m., and I just finished getting some projects done in my residence hall commons to hopefully move us toward being ready this Friday for Fall Arrival and Welcome Week.

Every year, I say I am not going to do this to myself, and every year, that promise to myself and my family falls flat on its face, exhausted, sighing, and maybe even snoring. But despite being really, really tired, and somewhat overworked, I find a strange energy in being here and I know in my heart that it is something that I am both good at and meant to do.

In his book Wherever you Go, There You Are, Buddhist author and mindfulness guru Jon Kabat-Zinn tells the story of Buckminster Fuller, who contemplated suicide one night after business failures got him feeling that people would be better off without him.

As Kabat-Zinn recalls the situation, Fuller instead decided to live his life as if he had died, to divorce himself from investing his emotional energy, time and effort in particular outcomes, and instead to do the things he knew how to do because it made sense, and was in service to the universe.

Working in higher education requires a similar mindset. Not so much from shooting for certain outcomes (this is pretty much the point of education in general) but instead by accepting that in the process of learning, the teacher isn’t the product. It’s not really even the information. It’s the process.

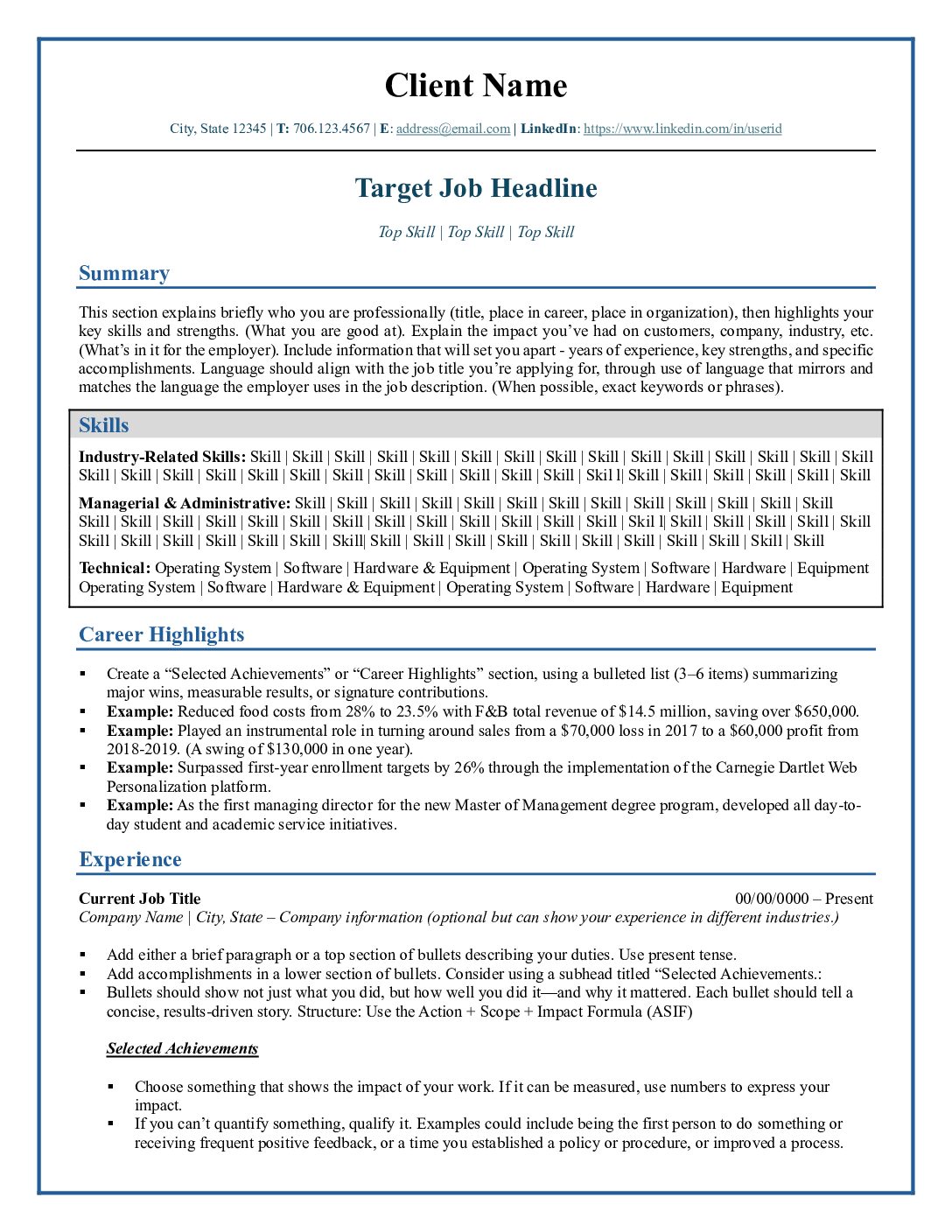

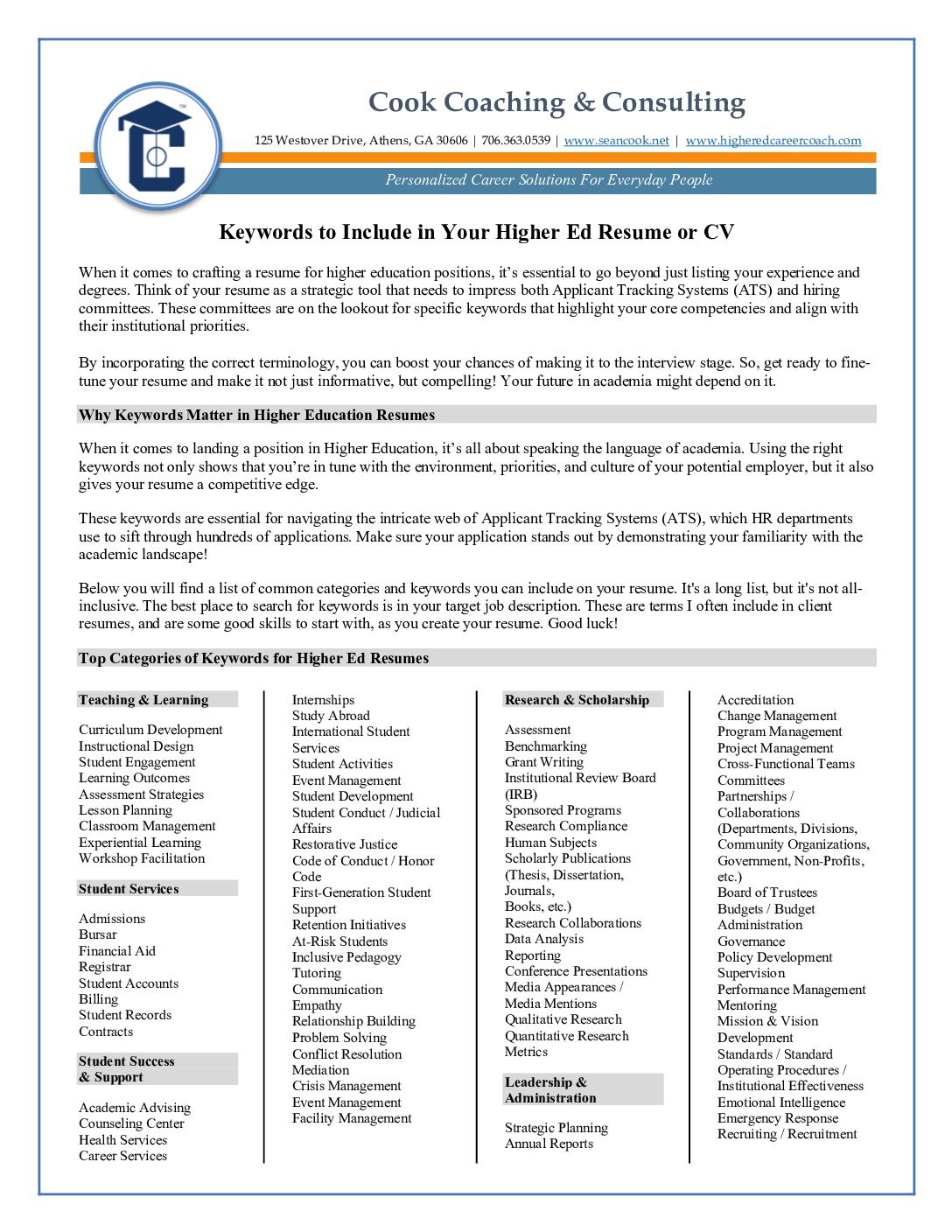

In my department, I am often involved in the interview and hiring processes, and so I’m regularly asked by candidates the usual sorts of questions that candidates ask to see if they will be a good match for the position, or to gauge if they will fit in well with our organizational culture. In answering these questions I spend less time talking about skill sets. . . they are on the resume, or they aren’t. . . and by the time the interview happens, whether a candidate has at least the basic aptitude for the job has pretty much been settled.The resume gets you the interview, the interview gets you the job, and your approach to the job very much determines whether you will do the job, or the job will end up doing you.

It shouldn’t surprise candidates, then, that hiring committees are more interested in determining “fit,” than looking at a portfolio of your previous work, or hearing that you are a superstar of some sort when it comes to one aspect or another of the job.

When interviewees ask “what are you looking for in a candidate?” some seem surprised when I reply that I am not looking for a particular skill set, or something obvious, like being a team player, but instead for someone who understands that working in higher education is a lifestyle, not just a job, and that the people who are most successful are those that can see beyond what they want from a situation and instead can clearly see where they fit into the big picture. In short, those who understand that it’s about the process, it’s not about them.

So, returning to the idea of “fit,” it’s perhaps not as nebulous as one might assume. If you spend your time asking questions like “What should I be doing right now?,” “How will my actions affect others?,” and “What makes the most sense in this situation?,” you are beginning to understand your “fit” at the university, in the career field, and maybe, as well, in the universe.